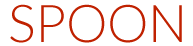

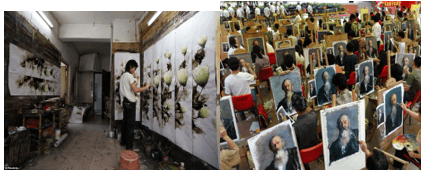

SEEING A MONA Lisa on every corner can be a bit surreal while walking around Dafen Village in China. There, for over 20 years, armies of painters have been churning out affordable knockoffs of priceless works. Italian photographer Susetta Bozzi documented the one-time farming village turned global art reproduction epicenter after it was swallowed by the megacity of Shenzhen.

“The reproductions are reasonably accurate representations of the original paintings, but there is always something — how to say? — out of place,” Bozzi says via email. “Often clients ask to change the colors, the background, to fit the color scheme of their house. As for the original work I haven’t seen anything really artistic. It seems to me that they produce stuff that can be easily sold.”

The rip-off revolution kicked off in 1989 when Hong Kong entrepreneur Huang Jiang arrived. Housing for his fleet of apprentices was cheap in the rural enclave, but not too far from the shipping ports of southern Guangdong. Contracts with western retailers soon followed.

Starving artists flooded Dafen to feed a hungry market. Jiang and inspired copycats nurtured the industry into a multi-million, multinational behemoth of questionable taste. Shenzhen was growing as well, leaving government officials torn. They liked the prospect of a successful bootlegging enterprise but not the underperforming farmlands. Buildings were razed and Dafen Village rebuilt as a shining example of both urban planning and culture.

“To do van Gogh’s Sunflowers, the most popular work of art, it takes about one-and-a-half days,” says Bozzi. “For more simple ones, if they are employing factory-style production techniques, it takes five hours on average for each painting.”

The cost of the burgeoning reproduction industry mirrors other facets of China’s explosive growth. Painters toil for long hours to meet quotas. Some receive monthly stipends, some are lucky enough to be boarded by their galleries. The less fortunate workers are housed in factory dorms or get sardined into tiny studios where they live and work.

“Most of them are art academy graduates who couldn’t make a living and opted for the commercial work. They are more like ‘factory workers’ than artists,” says Bozzi.

Growing up, Bozzi, a native of northern Italy, found work in the graphics department of a Roman newspaper after school. Following design led to employment with a publishing house, then a travel magazine. Later she decided to go freelance, which allowed her and her journalist husband to relocate to India in 1992. Ten years later the couple moved to Beijing.

“Being in a new country meant starting all over again, looking for clients, etc. I didn’t want to do that,” she says. “Photography was in the back of my mind for years. I used it occasionally for my design work, but I never thought it could become a profession. It did.”

China was booming at the time, in the early aughts. While Bozzi missed the quiet intensity of India she was thrilled by Beijing’s pace and relative ease of living. Hundreds of miles south Dafen was thriving, home of up to 60 percent of the world’s oil painting trade. Bozzi and her collaborator, a journalist who first encouraged her to take up photography, took a trip to check out the scene.

The following year the global economy collapsed. Everything was impacted, including the need to buy a shipping container stuffed with imitation Baroque masterpieces. While western purchases tanked alongside the stock market, a newly affluent Chinese middle-class stepped in.

“A report said that exports fell by more than 50 percent because of a collapse in Western orders,” Bozzi says. “Now the focus has shifted to the domestic Chinese market and the Western painting reproductions are increasingly being replaced by Chinese traditional art.”

Time will tell whether Dafen can regain its export business. And time will tell where Bozzi and her husband go next; they’re set to stay in Beijing for at least another year. Until then, she’s shooting a project on pollution in the outskirts of her adopted city and dreaming up ways to incorporate her years of design experience with her newfound career.

“I think, sometimes, cheap and fake can be fun,” she says. “I was actually tempted to buy one myself: a big painting of Napoleon Bonaparte on a horse! I didn’t buy it though.”